I don’t imagine this is something a person who hasn’t been through it can easily understand. With most other medical situations – say, for example, an infection that’s successfully treated, or the hernia-repair surgery I had a few months ago – when it’s over, it’s over. Cancer is never over, not even if remission continues into the long term. There’s always the possibility it could return.

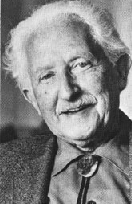

I don’t imagine this is something a person who hasn’t been through it can easily understand. With most other medical situations – say, for example, an infection that’s successfully treated, or the hernia-repair surgery I had a few months ago – when it’s over, it’s over. Cancer is never over, not even if remission continues into the long term. There’s always the possibility it could return.Here’s another quote from Glenna Halvorson-Boyd, from Dancing in Limbo: Making Sense of Life after Cancer (which I’ve now finished reading). Here, she shares a long-term survivor’s perspective – reflecting also the perspective of others, that she’s learned about through a number of interviews:

“At some point, those of us who have survived cancer stop wondering why it happened. We get over the posttreatment letdown. We tolerate our fears of recurrence in the full knowledge that there is no sure cure. Our relationships are renewed on current terms. Life goes on.

While our preoccupation with cancer fades, our awareness of mortality remains. That heightened awareness guides our lives, whether we recognize it or not. It creates anxiety, but it also reminds us that we are alive. Our time on earth is short and precious. This is the stuff of great art and trite greeting cards. Only a writer of Franz Kafka’s perverse gifts can get away with stating the obvious, ‘The meaning of life is that it stops.’ When we use a brush with death to refocus our lives in more authentic and meaningful ways, we are making the best of the situation, to be sure, but we are not romanticizing our misfortune. Cancer is not glamorous. Surviving cancer is neither romantic nor heroic. It is our good fortune, and it is forever a part of our lives. We may feel stronger for having endured the trials, or we may feel more vulnerable. Probably we feel both, on alternate days or even at the same time. Sometimes we know that ‘sadder but wiser’ is a cliché because it is true....

For some of us, having had cancer means that we don’t have time to waste; for others of us, it means that wasting time is our greatest luxury. For some, it means pushing to achieve our ambitions; for others, it means releasing ourselves from worldly ambition. As life goes on, we each sort out what it means to be a survivor.”

For some of us, having had cancer means that we don’t have time to waste; for others of us, it means that wasting time is our greatest luxury. For some, it means pushing to achieve our ambitions; for others, it means releasing ourselves from worldly ambition. As life goes on, we each sort out what it means to be a survivor.”– Glenna Halvorson-Boyd and Lisa K. Hunter in Dancing in Limbo: Making Sense of Life After Cancer (Jossey-Bass, 1995)

At the time she was writing, Glenna was reflecting back on more than ten years’ experience as a mouth cancer survivor. She had surgery that removed a part of her tongue as well as other tissue inside her mouth, and she had to learn how to speak again. Unlike me, cancer has left Glenna with a continuing disability, but the change she’s talking about is deeper than the merely physical. It’s a matter of soul.

I’m especially struck by what she says in the last paragraph, above, with respect to ambition. Some survivors want to aggressively pursue some long-deferred dream. Others want to shed worldly cares and learn to live as slowly and deliberately as Thoreau did beside Walden Pond. I think I’m somewhere in between. Some days, I want to go seek a call to some tall-steeple church and write a bestselling book. Other days, I just want to settle in where I am, be as good a husband and father as I can be, and simply try to live as authentically as I can. At this stage in my survivorship, I’m experiencing major ambivalence.

Here at our little cabin in the woods, ever since Claire ran out of vacation days and had to return home, I’ve been feeling that tug in two different directions. I’ve got some major writing projects in the works – most urgently, an overdue third installment of a preachers’ commentary on Cycle A of the Revised Common Lectionary. CSS Publications is going to combine this manuscript with books I’ve already written on Cycle B and Cycle C, and bring them out as a single volume. This morning, I finished my draft of Cycle A, and – once I drive into Plattsburgh, to my favorite wireless hot spot in the Borders bookstore café – I’ll e-mail it off to my editor. I’ve still got a good bit of work yet to do, on some additions the publisher has requested for the previous two volumes. It will be a good feeling to finally finish that multi-year project, which I began before my cancer diagnosis. I just may be able to finish it before my vacation ends in a couple of weeks.

I have to admit, though, I don’t have quite the fire in my belly for this project as I did when I began it. It’s all part of that ambivalence I’m feeling. Do I want to be one of those survivors Glenna talks about, who’s eager to “achieve worldly ambitions”; or, would I rather “release myself from worldly ambitions?” I’m still trying to figure that one out.

I have to admit, though, I don’t have quite the fire in my belly for this project as I did when I began it. It’s all part of that ambivalence I’m feeling. Do I want to be one of those survivors Glenna talks about, who’s eager to “achieve worldly ambitions”; or, would I rather “release myself from worldly ambitions?” I’m still trying to figure that one out.Maybe I’m having an experience similar to that of a testicular cancer survivor named Neil, whose story Glenna tells:

“Another cancer survivor described his cancer experience as an ‘early midlife crisis.’ Neil was thirty-two when he was diagnosed with testicular cancer twenty years ago. Although the prospects for a cure are quite good today, back then he faced almost certain death. Neil fought for his chemotherapy and became one of the early successes in the treatment of testicular cancer. When faced with death, he took charge of his life. As he puts it, ‘At thirty-two, I woke up to the fact that I’m going to die, and... I don’t want to waste my time. So you recognize that your time is limited and precious, and that you... have some control over it.’” (p. 147)

Some people go out and buy a red sportscar to celebrate their mid-life crisis. I got lymphoma.

I should have bought the sportscar instead.

I should have bought the sportscar instead.